|

|

There's a lot more to NEW

ORLEANS - the "Big Easy," the "city that care forgot" - than its tourist

image as a nonstop party town. The mixture of cultures and races that

built the city still gives it its heart; not "easy" exactly, but quite

unlike anywhere else in the States - or the world. There's a lot more to NEW

ORLEANS - the "Big Easy," the "city that care forgot" - than its tourist

image as a nonstop party town. The mixture of cultures and races that

built the city still gives it its heart; not "easy" exactly, but quite

unlike anywhere else in the States - or the world.

New Orleans began life

in 1718 as a French-Canadian outpost, an unlikely set of shacks on a

marsh. Its prime location near the mouth of the Mississippi River led to

rapid development, and with the first mass importation of African

slaves, as early as the 1720s, its unique demography began to take

shape. Despite early resistance from its francophone population, the

city benefited greatly from its period as a Spanish colony between 1763

and 1800. By the end of the eighteenth century, the port was

flourishing, the haunt of smugglers, gamblers, prostitutes and pirates.

Newcomers included Anglo-Americans escaping the American Revolution and

aristocrats fleeing revolution in France. The city also became a haven

for refugees - whites and free blacks, along with their slaves -

escaping the slave revolts in Saint-Domingue.

As in the West Indies,

the Spanish, French and free people of color associated and formed

alliances to create a distinctive Creole culture with its own traditions

and ways of life, its own patois, and a cuisine that drew influences

from Africa, Europe and the colonies. New Orleans was already a

many-textured city when it experienced two quick-fire changes of

government, passing back into French control in 1801 and then being sold

to America under the Louisiana Purchase two years later. Unwelcome in

the Creole city - today's French Quarter - the Americans who migrated

here were forced to settle in the areas now known as the Central

Business District (or CBD) and, later, in the Garden District. Canal

Street, which divided the old city from the expanding suburbs, became

known as "the neutral ground" - the name still used when referring to

the median strip between main roads in New Orleans. As in the West Indies,

the Spanish, French and free people of color associated and formed

alliances to create a distinctive Creole culture with its own traditions

and ways of life, its own patois, and a cuisine that drew influences

from Africa, Europe and the colonies. New Orleans was already a

many-textured city when it experienced two quick-fire changes of

government, passing back into French control in 1801 and then being sold

to America under the Louisiana Purchase two years later. Unwelcome in

the Creole city - today's French Quarter - the Americans who migrated

here were forced to settle in the areas now known as the Central

Business District (or CBD) and, later, in the Garden District. Canal

Street, which divided the old city from the expanding suburbs, became

known as "the neutral ground" - the name still used when referring to

the median strip between main roads in New Orleans.

Though much has been

made of the antipathy between Creoles and Anglo-Americans, in truth

economic necessity forced them to live and work together. They fought

side by side in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, the final battle of the

War of 1812, which secured American supremacy in the States. The

victorious general, Andrew Jackson, became a national hero - and

eventually US president; his ragbag volunteer army was made up of

Anglo-Americans, slaves, Creoles, free men of color and Native

Americans, along with pirates supplied by the notorious buccaneer Jean

Lafitte. Though much has been

made of the antipathy between Creoles and Anglo-Americans, in truth

economic necessity forced them to live and work together. They fought

side by side in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, the final battle of the

War of 1812, which secured American supremacy in the States. The

victorious general, Andrew Jackson, became a national hero - and

eventually US president; his ragbag volunteer army was made up of

Anglo-Americans, slaves, Creoles, free men of color and Native

Americans, along with pirates supplied by the notorious buccaneer Jean

Lafitte.

New Orleans' antebellum

"golden age" as a major port and finance center for the cotton-producing

South was brought to an abrupt end by the Civil War. The economic blow

wielded by the lengthy Union occupation - which effectively isolated the

city from its markets - was compounded by the social and cultural

ravages of Reconstruction. This was particularly disastrous for a city

once famed for its large, educated, free black population. As the North

industrialized and other Southern cities grew, the fortunes of New

Orleans took a downturn.

Jazz exploded into the

bars and the bordellos around 1900, and along with the evolution of

Mardi Gras as a tourist attraction, breathed new life into the city. And

although the Depression hit here as hard as it did the rest of the

nation it also heralded the resurgence of the French Quarter, which had

disintegrated into a slum. Even so, it was the less romantic duo of oil

and petrochemicals that really saved the economy. The city now finds

itself in relatively stable condition with a strengthening economy based

on tourism. Jazz exploded into the

bars and the bordellos around 1900, and along with the evolution of

Mardi Gras as a tourist attraction, breathed new life into the city. And

although the Depression hit here as hard as it did the rest of the

nation it also heralded the resurgence of the French Quarter, which had

disintegrated into a slum. Even so, it was the less romantic duo of oil

and petrochemicals that really saved the economy. The city now finds

itself in relatively stable condition with a strengthening economy based

on tourism.

One of New Orleans'

many nicknames is "the Crescent City," because of the way it nestles

between the southern shore of Lake Pontchartrain and a dramatic

horseshoe bend in the Mississippi River. This unique location makes the

city's layout confusing, with streets curving to follow the river, and

shooting off at odd angles to head inland. Compass points are of little

use here - locals refer instead to lakeside (towards the lake) and

riverside (towards the river), and using Canal Street as the dividing

line, uptown (or upriver) and downtown (downriver).

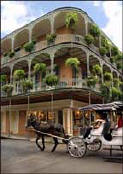

Most visitors spend

most time in the battered, charming old French Quarter (or Vieux

Carre), site of the original settlement. The heartbreakingly

beautiful French Quarter is where New Orleans began in 1718. Today,

battered and bohemian, decaying and vibrant, it's the spiritual core of

the city, its fanciful cast-iron balconies, hidden courtyards and

time-stained stucco buildings exerting a haunting fascination that has

long caught the imagination of artists and writers. Official tours are

useful for orientation, but it's most fun simply to wander - and you'll

need a couple of days at least to do it justice, absorbing the jumble of

sounds, sights and smells. Early morning in the pearly light from the

river is a good time to explore, as sleepy locals wake themselves up

with strong coffee in the neighborhood patisseries, shops crank open

their shutters and all-night revelers stumble home. Most visitors spend

most time in the battered, charming old French Quarter (or Vieux

Carre), site of the original settlement. The heartbreakingly

beautiful French Quarter is where New Orleans began in 1718. Today,

battered and bohemian, decaying and vibrant, it's the spiritual core of

the city, its fanciful cast-iron balconies, hidden courtyards and

time-stained stucco buildings exerting a haunting fascination that has

long caught the imagination of artists and writers. Official tours are

useful for orientation, but it's most fun simply to wander - and you'll

need a couple of days at least to do it justice, absorbing the jumble of

sounds, sights and smells. Early morning in the pearly light from the

river is a good time to explore, as sleepy locals wake themselves up

with strong coffee in the neighborhood patisseries, shops crank open

their shutters and all-night revelers stumble home.

The Quarter is laid out

in a grid, unchanged since 1721. At just thirteen blocks wide - smaller

than you might expect - it's easily walkable, bounded by the Mississippi

River, Rampart Street, Canal Street and Esplanade Avenue, and centering

on lively Jackson Square. Rather than French, the famed architecture is

predominantly Spanish colonial, with a strong Caribbean influence. Most

of the buildings date from the late eighteenth century, after much of

the old city had been devastated by fires in 1788 and 1794. Commercial

activity - shops, galleries, restaurants, bars - is concentrated in the

blocks between Decatur and Bourbon. Beyond Bourbon, up towards Rampart

Street, and in the Lower Quarter, downriver from Jackson Square, things

become more peaceful - quiet, predominantly residential neighborhoods

where the Quarter's gay community lives side by side with elegant

dowagers and scruffy artists. And it is in this area that you will find

the center of Southern Decadence activities. The Quarter is laid out

in a grid, unchanged since 1721. At just thirteen blocks wide - smaller

than you might expect - it's easily walkable, bounded by the Mississippi

River, Rampart Street, Canal Street and Esplanade Avenue, and centering

on lively Jackson Square. Rather than French, the famed architecture is

predominantly Spanish colonial, with a strong Caribbean influence. Most

of the buildings date from the late eighteenth century, after much of

the old city had been devastated by fires in 1788 and 1794. Commercial

activity - shops, galleries, restaurants, bars - is concentrated in the

blocks between Decatur and Bourbon. Beyond Bourbon, up towards Rampart

Street, and in the Lower Quarter, downriver from Jackson Square, things

become more peaceful - quiet, predominantly residential neighborhoods

where the Quarter's gay community lives side by side with elegant

dowagers and scruffy artists. And it is in this area that you will find

the center of Southern Decadence activities.

On the fringes of the

French Quarter, the funky Faubourg Marigny creeps northeast from

Esplanade Avenue, while the Quarter's lakeside boundary, Rampart Street,

marks the beginning of the historic, run-down African-American

neighborhood of Tremé. On the other side of the Quarter, across Canal

Street, the CBD (Central Business District), bounded by the river and

I-10, spreads upriver to the Pontchartrain Expressway. Dominated by

offices, hotels and banks, it also incorporates the revitalizing

Warehouse District and, towards the lake, the gargantuan Superdome. A

ferry ride across the river from the foot of Canal Street takes you to

the suburban west bank and the residential district of old Algiers.

Back on the east bank,

it's an easy journey upriver from the CBD to the Garden District, an

area of gorgeous old mansions, some of them in delectable ruin. The

Lower Garden District, creeping between the expressway and Jackson, is

quite a different creature, its run-down old houses filled with

impoverished artists and musicians. The best way to get to either

neighborhood is on the streetcar along swanky St Charles Avenue, the

Garden District's lakeside boundary. You can also approach it from

Magazine Street, a six-mile stretch of galleries and antique stores that

runs parallel to St Charles riverside. Entering the Garden District,

you've crossed the official boundary into uptown, which spreads upriver

to encompass Audubon Park and Zoo. Back on the east bank,

it's an easy journey upriver from the CBD to the Garden District, an

area of gorgeous old mansions, some of them in delectable ruin. The

Lower Garden District, creeping between the expressway and Jackson, is

quite a different creature, its run-down old houses filled with

impoverished artists and musicians. The best way to get to either

neighborhood is on the streetcar along swanky St Charles Avenue, the

Garden District's lakeside boundary. You can also approach it from

Magazine Street, a six-mile stretch of galleries and antique stores that

runs parallel to St Charles riverside. Entering the Garden District,

you've crossed the official boundary into uptown, which spreads upriver

to encompass Audubon Park and Zoo.

In

August of 2005, the devastation which resulted from Hurricane

Katrina and the subsequent flooding of over 80% of the city

changed everything. However today, there are more

restaurants and hotels open than before the storm, with the

city's population at well over 90% of pre-storm levels.

And virtually anything that a tourist would like to do awaits

you. In

August of 2005, the devastation which resulted from Hurricane

Katrina and the subsequent flooding of over 80% of the city

changed everything. However today, there are more

restaurants and hotels open than before the storm, with the

city's population at well over 90% of pre-storm levels.

And virtually anything that a tourist would like to do awaits

you.

Weekend Passes are recommended to

save money and avoid waiting in line.

Got a question? Email us at

info@southerndecadence.net

Southern Decadence web site contents are

Copyright 2023 SouthernDecadence.net

Please read our copyright policy on the Press

and Media page regarding the use of this material.

|